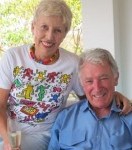

Co-founders John & Erica Platter reflect on the early years

What, as we’d say today, were we smoking? But we were young and carefree back then in 1978, when we gatecrashed a Cape wine scene steeped in centuries of knowhow and tradition, whose powerful dynasties had survived storms of all kinds and still owned their grand estates, a veritable landed gentry.

At a Nederburg Auction of the time, the current generation of titans, gnarled, sun-ripened, leathery men (they were all men then), stood up when their labels (gables, mountains, slave bells) came under the gavel; their winespeak made the mysteries of a vintage more mysterious still. Custodians of a formidable legacy, their forebears had coaxed nectar from these patches and despatched it across the seas to seduce the courts of Europe.

A sympathetic government provided the necessary authoritarian touches (protectionist quotas, fixed prices) to impart a sense of orderly timelessness. And the Cape’s magical, majestic scenery reinforced the idea of divine blessing.

We had no idea what we were letting ourselves in for

In we jumped, two young outsiders, both fresh from the deeply unsavoury byways of (‘liberal, independent’) journalism. We had no idea what we were letting ourselves in for.

I’d left United Press International, Erica the Sunday Express, and we’d bought a small vineyard in Franschhoek, the smallest of the then four La Provences, hankering after my family’s farming roots (in Northern Italy and Kenya). I drove the grey clackety Massey Ferguson tractor, our son Cameron wriggling in my arms, and the 2-tonne bin behind piled high with steaming steen grapes, to the co-operative in the village and waited in the baking sun for my turn on the scales, to be eyed and graded by the imperiously monosyllabic Oom Piet in his raised perspex cage. He decided our bank balances for the next season with the flick of a finger.

To help ward off penury, Erica and I continued to write: she TV reviews, and I a weekly column for the Rand Daily Mail, interviewing wine characters, profiling their wines. It was a wonderful education, but hardly lucrative.

And then Hugh Johnson produced his Pocket Wine Book. And we read it admiringly and thought: Let’s try to do something like this! Hugh’s elegant literary style is matchless. But by being what we were (and remain), inquiring journalists – we could have a go at assembling a modest local version of his global compendium. We’d approach it as reporters rather than judges, recording as many of the why, where, when and how specifics as possible. And we’d feature thumbnail sketches of the winemakers to bring their wines to life.

So his guide became our guide. Hugh’s earlier book Wine, already a classic, was inspirational too; how could anyone read it and not want to make their own wine? We did – tramping piles of (illicit) sugar and muscat grapes into La Platitude 1978, bottled by Charles Back. We drank the last of it 30 years later: very amber, but gloriously meaningful.

“He’s wasting his time – and your money."

The first setback to our plans – after Erica sweet-talked our bank manager into extending a risky overdraft to pay the printer – came from the industry Big Brother itself, the KWV. Innocently, we thought they’d welcome more wine information for consumers. But they refused to help us even with a list of producers, pronouncing: ‘Your book will be out of date before it’s printed.’

Next, a compositor phoned us late one night from the printer’s. He asked Erica: “Who’s writing this pamphlet?” She said: ‘My husband, why? And by the way it’s a book.’

“He’s wasting his time – and your money. It’s so BORING!’

Erica, indignantly: “It’s not a novel, it’s a reference book!” But we were rattled.

We bashed out every word on a typewriter in those pre-PC days; Erica edited every line; I tasted every wine myself, invariably more than once. We outsourced only the printing. Sales, promotion, distribution: everything else we did ourselves - a home industry.

There wasn’t a single chardonnay grown in South Africa then. Cold fermentation was a work in progress, though the centrifuge was already ‘homogenising’ hundreds of wines into soulless cleanliness; barrel – and malolactic - fermentation of whites was still to come. Sanctions kept the industry isolated – and defensive. But wine drinkers were thirsty for information. To our relief the guide took off and flew onto the stores’ top-seller lists, where it’s remained.

From a few hundred wines, we grew to several thousand. The wear and tear on my palate, constantly re-calibrated each year, meant the one-man band became a tasting team. First member was Angela Lloyd, still the grande dame.

We did not claim to taste ‘blind’ and that’s still the way. Platter is a guide not a competition result. We held that labels, price, and various objective criteria, were part of the mix we wanted for our overall assessment after a subjective tasting. Laboratory tastings have their place, as do white-coated blind judgings. But their results are not definitive or infallible either – because wine’s like that. And a single taster may even be more interesting and useful to consumers than a mixed panel tending toward a mean, if, like a film reviewer say, his or her tastes coincide with one’s own.

Meantime, we’d moved from Franschhoek, to establish Delaire and then Clos du Ciel; I planted vineyards (endless pleasure) and made our own wines (endless head-scratching). I could write from inside, from the ground up. Though I tried to remain a dispassionate outsider too...

The Mandela years gifted a fresh start

Which is why the adversarial encounters sometimes flowed more than they ebbed. New to the scene we might have been at the outset but plainly the controlling body of the wine establishment was the fox in charge of the henhouse - and as independent wine journalists our first duty was to the consumer, not producers or ‘the industry’. We obviously managed to over-stay our welcome with our friends at the KWV who – after the guide had been enthusing and informing local drinkers for two decades – felt it necessary to brand us ‘traitors to the wine industry’ - a badge of honour, we thought. But that’s history and we’ve shared many a glass with them before and since.

As the end of sanctions approached, we were caught up in the global wine revolution. The Mandela years gifted a fresh start, and South African wine, as a ‘breed’, became fit for purpose in the new age. Gone were the constricting fiats on quotas and prices. Space opened for new wineries, regions, varieties, labels, investors, speculators. We’re now seeing the full range: swank and bling; and great wine too made in a shed at the end of rutted road by a youngster with dreams... Bring them all on, we say.

Looking back, were we sad, after 20 years, to hand over to the present publishers? The book, our child, was ready to fly the coop – and so were we, freed for new challenges, including the all-Africa wine book we’d longed to write.

Platter’s Guide has simply gone from strength to strength. And though we no longer take the bows (and brickbats!) we continue to applaud proudly from the sidelines.